As I’ve acquired and planted out high-quality mulberry cultivars, I’ve found a major challenge in growing this fruit that’s been very little reported: many of the top quality varieties are extremely sensitive to root-knot nematodes.

Parasitic root-knot nematodes (hereafter just referred to as “nematodes”) are tiny microscopic worms which are abundant in sandy Florida soils (as they are in many warm climates worldwide). These little worms burrow into the roots of many kinds of crop plants, causing bumpy, knobby lesions, and impairing the ability of the roots to absorb water and nutrients from the soil.

For many years, my standard method to propagate mulberries has been by cuttings – it’s a quick and easy way to produce large numbers plants of a good variety. For years I’ve puzzled over why some of the cutting-grown mulberry trees I planted out in the ground would take right off and grow rapidly into a big tree, while plants of other mulberry varieties struggled weakly for years, never really gaining much size, and eventually died altogether.

The issue really came to a head in the last few years when I acquired the cultivar which I consider the best-flavored mulberry variety ever, ‘Himalayan’, and I excitedly planted out two cutting-grown trees of it in the ground. Both trees showed the same pattern after I planted them out: they made a small initial burst of new shoots and leaves, then growth stalled, and each tree declined and eventually died altogether. Puzzled and disappointed, I dug up the dead trees and found the roots were completely riddled with the bumpy, knobby galls characteristic of root-knot nematode damage. I had never heard of nematodes being a problem for mulberries.

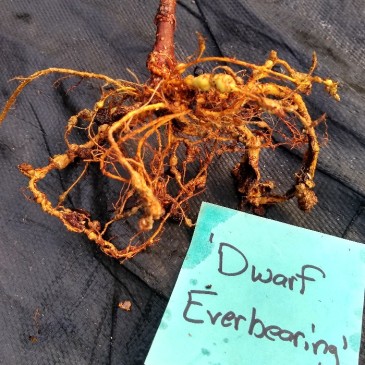

So I checked the roots of some of my other mulberry cultivars which had been growing more slowly than I thought they should: ‘Dwarf Everbearing’, ‘Green White’, and ‘Cookes Select Pakistan’. All had roots riddled with nematode lesions.

Thinking back, I remembered how in previous years I’d planted out own-root plants of ‘Pakistan’ and ‘White’, only to watch them struggle along for several years without ever gaining much size until they eventually died. I didn’t check their roots for nematode damage, but I have a hunch that was the problem. I no longer have either of those varieties in my collection, but the variety ‘Cooke’s Select Pakistan’ I do have is reported to be a seedling of the original ‘Pakistan’ cultivar, and the Cookes plant is suffering from nematodes, so likely that was the issue with the parent cultivar as well.

I wish I’d known.

I already knew nematodes were a problem for figs, and I have a project testing nematode-resistant Ficus species as potential rootstocks for figs. Looks like if we want to grow extremely high quality mulberry varieties like ‘Himalayan’ in areas with nematode pressure, we’ll have to do the same process – we need to find mulberry cultivars that are both nematode-resistant, and graft-compatible with the good nematode-sensitive varieties.

Looking online, I don’t find a lot of information about nematodes being a problem for mulberry fruit production. Most of the information which is available is from India, where farms grow mulberry leaves to be fed to silkworms to produce silk. I did find a couple of reports describing how researchers in India tested different varieties of mulberry for nematode sensitivity, and they found some cultivars were indeed much more resistant than others. Since they’ve already done that work, it would be nice to be able to use their best-performing cultivars as rootstocks, but importing varieties across international borders is difficult. So I decided to start from scratch, and do the same process here.

I did a very small experiment: in spring 2019, in the same area where one of the ‘Himalayan’ mulberry trees had died from nematode damage, I planted out a number of small plants of eight different cultivars of mulberry. It was just one plant of each cultivar, and the varieties I used were ones that I happened to have available. I put the plants in the ground on about a two foot spacing from each other, and I did not mulch this test bed, because mulch reportedly can suppress nematodes. After about a year, in early June 2020, I dug up the plants and examined the roots for nematode damage.

To be clear, this was an extremely small planting. It’s possible that there could have been variations in nematode populations across the small area they were planted in, which could affect the damage received. A better test would include multiple plants of each cultivar, with plants of all cultivars mixed across the test site (rather than grouping plants of each cultivar together). But a small experiment is better than no experiment. Here’s what I found.

The varieties I tested were:

- ‘Dwarf Everbearing’ a very common variety in Florida nurseries. It is a small growing tree which can fruit multiple times a year, and starts ridiculously easily from cuttings, which undoubtedly contributes to its wide availability.

- ‘Edible Leaf‘ – A variety which Josh Jamison acquired from ECHO as a fruiting variety, but which turned out to be much better as an edible leaf vegetable (leaves must be cooked).

- ‘Sixth Street’ An excellent cultivar named after the location of the original tree on NW Sixth Street in Gainesville. It reliably stays dormant through the winter, and produces large quantities of excellent quality berries. Tree can grow rather large.

- ‘Mustang Thai’ My provisional name for a cultivar acquired at Mustang Market in Pinellas Park from a vendor who said it’s a Thai variety. Produces very large berries.

- ‘Illinois Everbearing’ A commonly cultivated mulberry from much further north than Florida.

- ‘Bryces Worlds Best’ Another one thought to be a Thai commercial cultivar, it produces heavy crops of large berries. This is the same one often called ‘Worlds Best’ in the nursery trade.

- ‘Olivers Wild Mulberry’ A wild or feral mulberry clone which Oliver Moore found thriving on his property.

- ‘318 Wild’ A seedling found growing wild on State Road 318.

Here’s how they scored, grouped by the level of nematode damage:

Extremely severe nematode damage: ‘Dwarf Everbearing’ (plant died)

Severe nematode damage: ‘Bryces Worlds Best’, ‘318 Wild’, ‘Thai Mustang’

Moderate nematode damage: ‘Edible leaf’

Trace of nematode damage: “Sixth Steet’, ‘Olivers Wild Mulberry’

No visible nematode damage: ‘Illinois Everbearing’

Although they were not included in this test plot, I can also rate the level of damage I’ve seen in other locations of several other varieties: ‘Himalayan’ suffered extremely severe nematode damage (the plants died), ‘Cookes Select Pakistan’ had severe damage, and ‘Green White’ had moderate nematode damage to its roots.

Based on the information I now have, out of all these, I think the prize for the most promising rootstock goes to mulberry variety ‘Sixth Street’. There are a couple of reasons: not only did this variety have virtually no nematode damage, but also the little plant I stuck into the ground made a particularly impressive root system – there were some large roots spreading out so far horizontally I had to chop them off.

Another advantage of ‘Sixth Street’ is that it’s an excellent fruiting cultivar in its own right. I can propagate large quantities of plants of this variety by cuttings, and I have the flexibility to use them either for rootstocks, or directly for distribution as a good fruit tree. And for any mulberry tree grafted on this as rootstock, if the scion ever gets killed (overzealous landscape workers armed with string trimmers are notorious for girdling trees), the tree will at least resprout as another good variety – not the intended variety, but still a good fruit producer.

Why not Illinois Everbearing, which had zero visible nematode damage, versus the trace of damage seen on ‘Sixth Street’ roots? First, the ‘Illinois Everbearing’ plant in this experiment didn’t grow as vigorously. But I’ve recently become of another potential drawback of this variety in my area.

On my property there’s a mature tree of ‘Illinois Everbearing’ that’s always been a reliable producer. This year featured the mildest winter in the twenty-plus years I’ve been in Florida, and something odd has happened: as of early June, the Illinois Everbearing mulberry is still mostly in its leafless winter dormant condition, with only a few leaves popping out here and there. The winter of 2019-2020 had only 268 chill hours (hours below 45F), while the historical average in my area is 471 chill hours each winter. Apparently the ‘Illinois Everbearing’ tree didn’t get enough chill hours to break winter dormancy. I’ve never seen this happen before with this tree, and I don’t know if the tree will eventually leaf out over the course of the summer, or if it will be able to stay alive in nearly leafless condition for many months until next winter brings more chill hours. If this cultivar were used as a rootstock, I wonder what would happen after a mild winter – would the dormant roostock inhibit the scion from pushing out growth? Maybe it wouldn’t be a problem, but to be safe I’d rather graft onto a rootstock that I know comes out of dormancy even after mild winters, and ‘Sixth Street’ does that reliably. With average temperatures rising due to human-caused climate heating, this is likely to be a recurring issue. (Update: the ‘Illinois Everbearing’ tree finally broke dormancy and leafed out during the second half of June 2020, about two months later than usual.)

Conversely, many mulberry varieties break dormancy too early in my area, pushing out tender new growth during warm spells in winter. I wonder if a rootstock which responds to a warm spell in January by breaking dormancy and getting its sap flowing, is then in danger of getting frozen out by freezing temperatures occurring in February. Of course, if the rootstock gets killed, the top of the tree will die shortly thereafter. One of the things about ‘Sixth Street’ that I’ve always appreciated is the fact that it reliably starts to break dormancy around the end of February, just as the danger of severe freezes is becoming minimal.

There’s another reason why I’m deciding to use ‘Sixth Street’ as a mulberry rootstock: I’ve already done some experiments with it for this purpose, and early results are promising. At the same time I was setting up this test plot in 2019, I didn’t want to wait a year for results before I could start grafting some of those excellent nematode-sensitive cultivars onto good rootstocks. I’ve had good results growing ‘Sixth Street’ here as a fruiting variety, and haven’t noticed nematode damage on its roots (although until this test I couldn’t be sure if maybe the spot where the big ‘Sixth Street’ tree just didn’t have nematodes.)

So last year in 2019, I grafted one plant each of varieties ‘Himalayan’ and ‘Bryces Worlds Best’ onto plants of ‘Sixth Street’. I then planted both in the ground, and both trees have made very impressive vigorous growth over the short period they’ve had their roots in the earth. After a year, the graft union of each tree is smooth, with no evidence of graft incompatibility.

If you are interested in getting material of variety ‘Sixth Street’, I often have this variety for sale in my nursery in Citra, local sales only, no shipping (quantity is low right now, but I should have more later in the year). Message me if you want to check availability. If you’re closer to Central Florida, Josh Jamison at the Heart Institute in Lake Wales has a small nursery which sometimes sells variety ‘Sixth Street’ – again, local sales only, no shipping. It will be at least a year before either of us has grafted mulberry trees available, but you can get ‘Sixth Street’ now if you want to try doing your own grafting.

In the coming years I’ll continue this experiment, adding other mulberry cultivars to the test, and for whichever cultivars show little nematode damage, I’ll try using them as rootstocks. And for any of those cultivars which show little to no nematode damage and which also make good fruit in their own right, I’ll know that I can produce own-root trees of them by cuttings, without bothering to graft them.

I should mention that while root-knot nematodes are widespread in Florida, they are not universal. They seem worst in sandy soils, but not as bad of a problem in clay or muck soil. And in extreme southeast Florida, the alkaline limerock soils of Dade County seem to not have much problem with nematodes, so people grow nematode-sensitive cultivars like ‘Himalayan’ there seemingly without problem. Even in the sandy soil areas of Florida, nematodes are apparently patchy – figs are generally sensitive to nematodes, and in some locations fig trees struggle from this problem, but in other sandy soil locations, figs grow into large, productive trees. But on my property the soils seem pretty will infested, as they are in many areas in Florida and other warm climate areas, so this is work that potentially could be useful in many regions.

Mulberry has tremendous potential as a fruit crop, and finding rootstocks which allow top-quality varieties like ‘Himalayan’ and ‘Bryces Worlds Best’ to grow in nematode-infested soils seems to be one of the key steps in making this tree much more widely grown as a fruit tree in Florida and similar climates.

To see related posts on this blog, check out these tags: #mulberry #Moraceae #grafting

You are killing it with your nematode research Craig. Keep up the good work. I sent you an email about this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much, Mike.

LikeLike

Hey there!

I wanted to chime in with some research I’ve been gathering as of late concerning soil microarthropods and wanted to send you down a rabbit hole concerning this. Rather than looking towards resistant rootstocks, I’m more inclined to look towards nematophagous microarthropods. There’s quite a bit of research coming out about these wee beasties and showing significant predation on nematode populations. Here’s a paper to get you started 😉

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5644927/

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wow, great tip, that looks promising! Thanks, Eliza.

LikeLike

This is wonderful! And that you can do real cutting-edge research with real potential benefits from a small homestead is inspiring!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Alder. Yeah, with both this and the fig nematode project, it’s pretty remarkable that what seems. like such an obvious need has been so neglected. They’ve been sufficiently neglected that even a very small scale homestead project can produce some advancement of knowledge on the subject.

LikeLike

I enjoyed reading your post and experiment. Thank you so much for sharing. My dad recently asked me to help him buy a mulberry tree and I ended up purchasing Pakistan variety. If down the road it doesn’t do well… At least I know it could be nematodes. I’ll have to look online to try and find sixth street.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Kelly, thanks for the positive feedback on the article. Years ago, I ordered a ‘Pakistan’ mulberry from Edible Landscaping nursery, and when it arrived I was surprised it was grafted, since mulberries are so easy from cuttings. I subsequently multiplied it by cuttings, and it was a cutting-grown plant that I put in the ground. Maybe those folks already knew about the nematode issue, and that’s why they were grafting them. Might be worth a close look at that ‘Pakistan’ you got to see if it’s already a grafted tree.

LikeLike

Wow. Did not know there were other Mulberry fanatics. Had a Pakustan at last house. Took cuttings, both new growth and old growth, but none took. Does anyone know where in the Sarasota or Manatee County areas that I could find a Pakistan or Himalayan? Just planted a conventional large leaved black, but would like other varieties. From article, can I conclude that Illinois Everbearing would not work here? Any other large berry everbearing? The standard tiny berry everbearing is not of much interest. Anyone try multigrafting on hearty rootstock?

Also interested in persimmons. Source for trees?

Thanks.

Jeff in Sarasota County

LikeLike

Hi Jeff, thanks for commenting. If you can find it, I’d suggest preferably searching out ‘Himalayan’ versus ‘Pakistan’, because I think the flavor of ‘Himalayan’ is several notches higher. Unfortunately the two varieties are frequently confused in the nursery trade, and sometimes you’ll be told that a nursery has “that Himalayan-Pakistan variety”. The cultivar I refer to as ‘Himalayan’ came from a cutting from a tree labeled as such at the Fruit and Spice Park in Homestead. But Pakistan is a lot easier to find in the nursery trade. In Sarasota, you might check with Sulcata Grove nursery – I don’t know if they actually have that variety, but they do have a diverse selection of fruit trees available. Also the FGCU Food Forest in Fort Myers had Pakistan when I visited them a few years ago. If you can communicate with someone there, they might let you take cuttings. Also you could try ECHO in Fort Myers.

I just put an update on this article that the Illinois Everbearing tree has finally leafed out in late June. I’ve heard of people getting it to grow and fruit in the equatorial tropics by stripping its leaves off periodically to simulate winter. I don’t know enough about how well it handles Central Florida conditions to say whether it’s a recommended variety there or not.

The places I mentioned for mulberries would also be good places to check for grafted persimmons. Reportedly ‘Hudson’ and ‘Triumph’ are the Asian (kaki) persimmon varieties with the lowest chill requirements.

LikeLike

Been ages since I was at Fruit and Spice Park. The curator spoke at one of our Rare Fruit Council meetings about 20 years ago describing putting the park back together after Hurricane Andrew. Bet they are good as ever by now.

Many thanks for the suggestion and best of luck. Just came across you for the first time. Bought house in Southern Sarasota County recently and the fruit tree planting is essential. Back in the hobby after being out of it for long time. Just planted 4 dwarf mango varieties and some other things. Have about 10 trees remaining on the shopping list.

Regards.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really appreciate this info, Craig! I’ve had a 6th Street tree here for probably 10 years and it’s growing and producing wonderfully. I got some cuttings from Bryce earlier this year and due to neglect on my part have only 1 left that is thriving in a pot. I was all set to plant it in the ground when I came across this unopened blog post in my email! Very helpful for me to now: start a new 6th street, cut my Bryce’s World’s Best in half and plant one in the ground and one in a large pot to wait to be grafted onto the 6th street at the right time. And lastly, maybe order one all set to go from either you or Josh! Josh is closer and it’s been awhile since I’ve been to HEART! Oh and I also have a dwarf everbearing from Oliver two years ago that I was finally getting ready to plant–now I’m considering what I would do with it, too? Graft it onto a 6th St, too? How does all this sound?

LikeLike

Those plans all sounds good, PC. I don’t yet know if ‘Sixth Street’ is the absolute best nematode-resistant rootstock for mulberries, but so far it seems at least a pretty good rootstock for them. (Some varieties might be more vigorous than ‘Sixth Street’) For any of those varieties you mentioned, in nematode-infested soil it definitely seems better to plant them grafted onto ‘Sixth Street’ roots rather than growing their own roots. Neither Josh nor I have yet figured out a method for efficiently doing large numbers of mulberry grafts with high success, so no guarantees of grafted plants being available anytime soon. The most reliable way I’ve found to graft mulberries is approach grafting, which is definitely not efficient to do in quantity.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We use crab shells around our figs and they are as healthy as can be. One of our neighbors said that’s what they did in the old days for nematodes around here. Looking into it further the crab shells promotes a hostile environment by feeding organisms that eat the nematodes. I wasn’t aware mulberries have issues with nematodes so now I will be using the shells around them as well! Thanks for the information!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Very interesting article, Craig – thanks for taking the time to do this. I’ve not noticed any nematode issues with the two varieties I’m growing: Tice and Pakistan, but that’s very dependent on everyone’s individual soil. I tend to get about 50% rooting success with cuttings on either variety and sell/plant them out of 3g. I would love to get Himalayan and World’s Best. Can I somehow get cuttings from you? I grow all kinds of fruiting plants, 5 types of jaboticaba, etc. Maybe you would be interested in trading.

LikeLike

Mystery solved! I am so ecstatic to find your great mulberry roots photo. I found those same orangey roots in my flowerbeds. I knew they weren’t healthy but I couldn’t find the plant they were coming from. Now, finally, I can confirm that it is my neighbor’s mulberry tree that is the cause of my failing plants. Good news; bad news, right? But at least I can try resistant plants and beneficial nematodes. Enjoyed reading about your mulberry tree experiment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mulberry trees seem to send out a lot of fairly shallow roots. One option would be to take a reciprocating saw with a long 12 inch blade, sticking it in the ground, and cutting along the property line to cut through any mulberry roots. Of course, check first to make sure you won’t be cutting any electrical lines, gas lines or other utilities.

LikeLike

Hello

Nice article. Didn’t know there were so many cultivars of mulberries. And also thanks for the nematode info. Didn’t know they were a problem for mulberries. Got 2 I’m planting this week. If you want to keep nematode problems down- plant french marigolds all around them. They excrete a chemical that kills root rot nematodes and is harmless to plants. Plus they repel ALOT of pests above the ground. I have them in all my gardens, strawberry patchs and some friut trees. I live in the panhandle about 90 miles west of Pensacola. Hope this helps some people and thanks, Ron.

LikeLike